I recently had a discussion with another mom about nitrates and nitrites in meat and their safety. She said that she buys nitrate-free products for her kids. She is a smart lady and wants to do the best for her family’s health, but she didn’t even understand what nitrate or nitrites are and sure didn’t know why they were added to meats.

I touched on nitrite a little bit in my processed meats post, but I thought a whole post about them might clear things up.

Question one. What is nitrate/nitrite?

Nitrates and nitrites are chemical groups, part of lots of compounds, both natural and man-made. They are a combination of a nitrogen atom and either two (nitrite; NO2) or three (nitrate; NO3) oxygen atoms. When it’s added in processed meats it is usually combined with sodium or potassium (you would see it as Sodium Nitrite on the ingredient statement). Nitrite (the one with 2 oxygens) is most commonly used in meats.

Nitrates and nitrites are chemical groups, part of lots of compounds, both natural and man-made. They are a combination of a nitrogen atom and either two (nitrite; NO2) or three (nitrate; NO3) oxygen atoms. When it’s added in processed meats it is usually combined with sodium or potassium (you would see it as Sodium Nitrite on the ingredient statement). Nitrite (the one with 2 oxygens) is most commonly used in meats.

I mentioned in a previous post the benefits of nitrite in the diet and linked to the video by Dr. Nathan Bryan.

Question two. Why is nitrite added to meats?

Good question. Have you ever heard of cured meats of meat curing? Curing meat requires nitrite. Some good examples of cured meats are ham, bacon, hotdogs, and pepperoni.

The nitrite in cured meats serves several purposes.

- It gives cured meats that pretty pink color and the color that lasts a long time (unlike fresh meat color).

- It gives cured meats their distinct flavor. (Think about how a ham tastes so different from a pork roast.)

- It protects the meat from organisms that cause spoilage and disease. Cured meats have a longer shelf life than most uncured meats. Nitrite directly prevents the growth of that nasty ol’ Clostridium botulinum, which is the bacteria that causes botulism (it’s also the organism used to make Botox, but that doesn’t mean we want it in our meat).

- It prevents the meat from going rancid and protects the flavor of the meat.

Many historians think that meat curing was discovered by accident when salt contaminated with nitrite was rubbed on meat. (Salt was one of the first ingredients added to meat).

Question three. Why do we have uncured or no nitrite/nitrate added products?

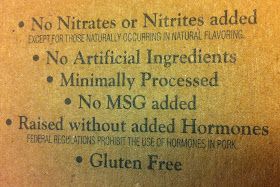

Natural and organic products have become very popular in the last few years. I covered this in one of my first blog posts. The definitions of Natural and Organic are regulated by USDA, and nitrates and nitrites are not permitted as an ingredient in products with those labels. If you try to make cured meat products like ham, bacon, or hotdogs without nitrite, the meat turns out a gray color and won’t have the typical cured flavor. Not so good.

Why don’t people want it?

When consumed in large quantities, nitrite can be toxic. Also, nitrite can combine with protein in meat at high temperatures and form nitrosamines, which are cancer-causing agents. Now, the amount of nitrite added in processed meats is very small and most processed meats are not cooked at those very high temperatures, so the level of nitrosamines formed is almost none. Processors also started adding the antioxidants, ascorbate (vitamin C) and erythorbate (structurally related to vitamin C), to cured meats to block the formation of nitrosamines. There has also been some scary stuff published that attempted to link hot dogs with cancer, but those studies have since been disproven.

So how do we get uncured ham and hotdogs that still look and taste like ham and hotdogs?

Remember in the processed meats post, I mentioned the video of the interview my friend Dr. Jeff Sindelar? He told us that people ingest most dietary nitrite from green leafy vegetables and not from processed meats. Technically, it’s nitrate (NO3) that is found in most vegetables, but it’s is converted to nitrite in when it comes into contact with the saliva in your mouth. These same vegetables and/or their juices can be added to Natural meats as a source of nitrite. Processors may also add harmless bacteria, called a starter culture, to convert the nitrate in the vegetables into nitrite.

But, why does it say “no nitrite or nitrate added” and “uncured”?

Because nitrate or nitrite is not added directly, the process of the traditional cured meats is altered, so the manufacturers are required to say that it is “no nitrate or nitrite added” or that it is “uncured”. A more accurate term would probably be “indirectly cured” or “naturally cured”.

So, is it better or worse than conventional cured meats?

The answer to that question is, “Yes.” If you feel very strongly about eating natural or organic products and don’t want to consume artificial ingredients, or if there are other claims that accompany the natural claim, like grass-fed or antibiotic free, that are important to you, then these products will allow you to still enjoy hot dogs and ham and other cured meats. Realize that the nitrite is still in the meat product. It just comes from a natural source.

One concern I have is that other ingredients, such as lactates, that help inhibit spoilage and fight off pathogenic organisms are not allowed in natural and organic meats, so they may be more susceptible to spoilage and are more dependent on processing techniques to guard against pathogens. You should be very careful to observe the use by dates and store them correctly. See my lunch box safety post for that info.

Natural and organic meats products are more expensive than traditionally-processed products, so the benefit of low cost protein is somewhat lost when you choose natural or especially organic.